For many the first course of study is to learn the names. Names facilitate communication and anchor our explorations. When one signs up for a botany field trip, it is expected that plants will be identified and named. I imagine most would be disappointed if they didn’t come away from a field excursion without learning the names of a few plants. I think that the stories of mosses can be told without the names but it can be argued that knowing the name of the plant you are talking about is a matter of respect–much like remembering the names of newly introduced acquaintances at a get-together. It can also be argued that for a group like mosses, you have to learn a lot about mosses just to begin naming them. Of course, the names we give to mosses are for us and not the mosses. This account records some of the different paths I explored while trying to name a local moss that found me one day during a run. Originally, much of this account was shared on the Kansas Native Plants Facebook page. I’ve cleaned those comments and posts up a bit. Perhaps following along the twists and turns of the adventure/struggle will give others the confidence to persevere in their efforts to learn a bit about mosses. Full disclosure–I’m no moss expert but I am enjoying getting to know the plants, they are fascinating. Let’s get started.

Back in August 2021, I had the opportunity to attend a Moss workshop in Maine put on by Jerry Jenkins of the Northern Forest Atlas Project at the Eagle Hill Institute. I had a great time learning from other moss folks although I’m not sure why we were learning mosses in Maine, mosses were hard to find. 😉

I returned with quite a few new skills, new confidence, and a more refined outlook on strategies for learning not just which mosses I was looking at but also the stories these mosses had to tell. Later that summer I was finishing up a run along this trail and at this bridge happened to look down and see a piece of bark covered with scraggly mosses that had fallen from this Black Willow.

Not impressive but there were three kinds of moss on this small piece of bark that I figured must have been growing over 10 feet up on the top of the trunk. (Turns out, I later found a liverwort on that piece of bark as well.). I put the bark in my pocket and finished my run. Based on the size of the strands of moss I thought I had a good idea of what I had picked up but I ended up with some surprises. By the way, one of the first things you want to figure out when working out a moss i.d. is what is the growth form: upright, single stems growing in a cushion (acrocarps) or sprawling, stringy, branched stems growing along the surface (pleurocarps). The mosses here are pleurocarps.

A short discussion on a/p

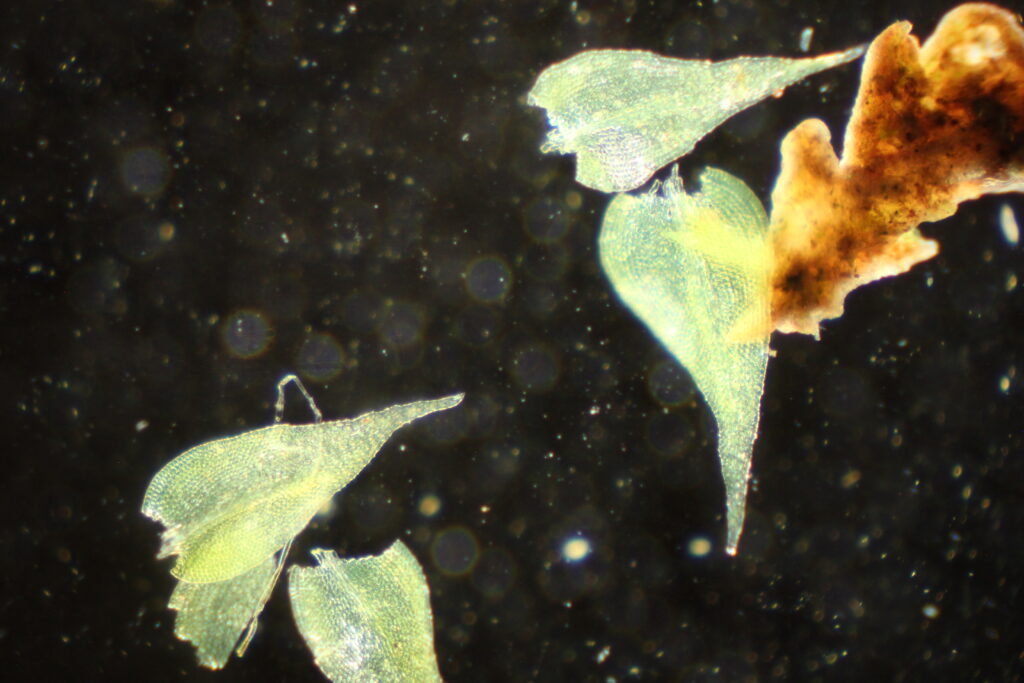

I’ll go through most of the steps that I took and the decisions I made to put some sort of an ID on this moss. For now, I’ll describe the steps I went through this first time–in the future when I encounter this moss things will be a bit different and I’ll be able to rely more on my hand lens since I know what to look for. The first thing I did was to strip off some leaves from the stem and put them under the microscope. This is one of the first steps and requires a bit of skill. Some folks strip off the leaves using two sets of microforceps. I like to cut the leaves off with the needlepoint of a tuberculum syringe while holding the stem with the forceps. The syringe point is razor-sharp. I collect the leaves and then examine them under the compound microscope. Here’s what they looked like.

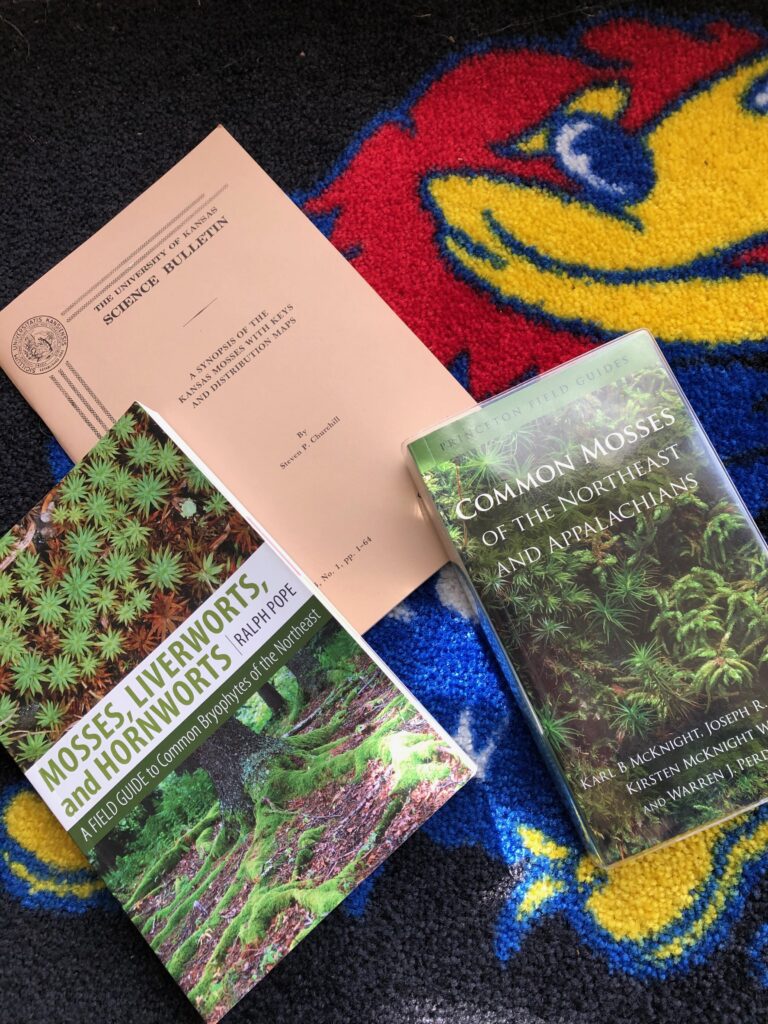

I usually start my search with this resource from the Princeton Field Guide Series. The authors worked hard to develop a series of keys that mostly rely on observations you can make with a hand lens although a microscope is helpful. After determining the growth form the next step is to determine leaf shape, whether or not a costa is present and what does it look like? Costa??? What’s that? Costa is a term used to describe a kind of midrib down the center of a leaf. So looking at the micrograph of the leaves above What shape would you describe these leaves and does it have a costa? BTW, the shape of the leave is where I always seem to get on the wrong track. How do you decide the difference between a lance shape, an oval shape, an ovate shape, or a tongue-shaped leaf? Each key author can have a different idea about these shapes that may not agree with your assessment–not a big difference but enough to lead you down the wrong path on the key. Until I’ve gone through the keys with different plants I make lots of mistakes as I try to interpret characters like the author. And guess what? This is even harder if this is the first moss you’ve examined closely. This is one of the areas you need to be ready to come back to and restart your search if the future keys don’t match up to your specimen.

One of the problems with using a guide like the Princeton guide is that it was written for the Northeast U.S.–not KS. So things might not work out. This is where having the list of KS mosses comes in handy. When I applied the keys in the Princeton Field Guide I tentatively assigned Leskea gracilescens (Necklace Chain moss) to my moss in question. It is tempting to stop here but you need more confirmation than coming to the end of the choices in a key. I looked up images on the internet for L. gracilescens. And at sites like this one for Ohio mosses the images for L. gracilescens weren’t matching up with my mystery moss. https://ohiomosslichen.org/moss-leskea-gracilescens/ I started having doubts about my tentative identification. One sticky point is that the dried moss images for L. gracilescens didn’t look anything like mine and on top of that the leaves on my moss were slightly but consistently larger. The tips of my leaves were more pointed and had this shaggy look to them in the dried stem. If not L. gracilescens then what could it be?

Now, I use every resource I can get my hands on and in today’s digital world, that is a lot. We owe so much to those who have gone before us and one example of that is that I can go to the KU or the KSU herbariums and download spreadsheets of moss collection data and put together a list of which mosses have been collected in KS. I’ve done that and have even created lists by county. Here’s the list I put together for Douglas County from the McGregor Herbarium at KU. https://docs.google.com/…/1qPPo4q4VXwzr1KQQsWO1…/edit…. The great thing about this is that at this stage of my knowledge, I can use this to limit my search to only about 75 moss candidates–a first filter. On top of that as we have discussed earlier this moss has a pleurocarp growth form so that eliminates the acrocarps—Now we are down to < 40 or so possibles.

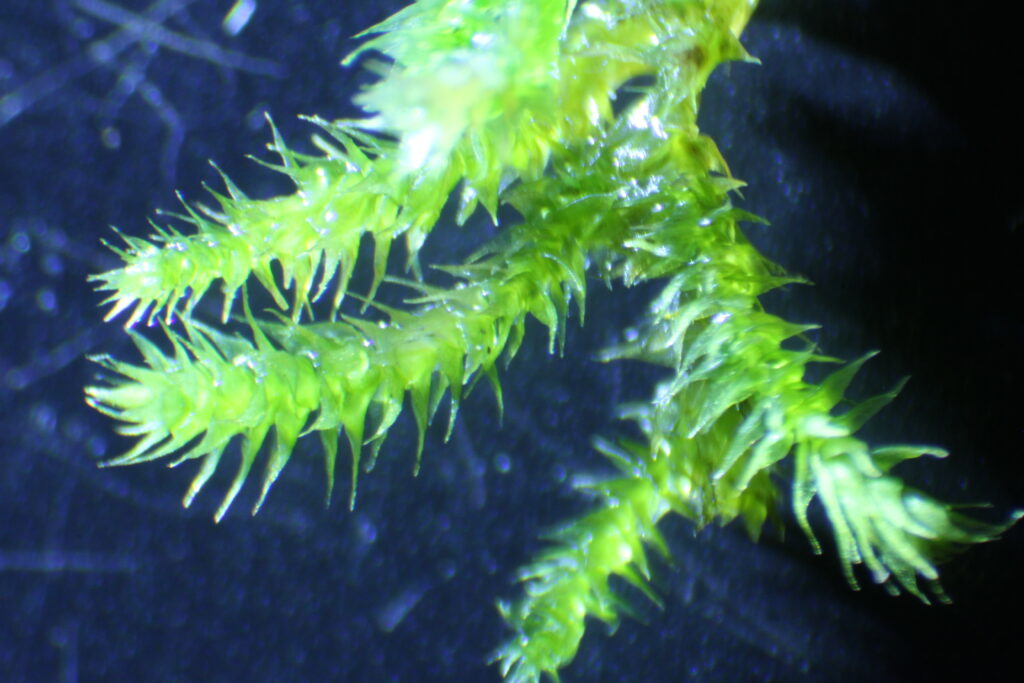

I have a copy of A Synopsis of the Kansas Mosses by Steven Churchill so I went to that next—but that has a more technical key. Still, perhaps I could figure it out. Real early in Churchill’s key, it asks about whether or not the cells of the leaf (microscope required) are papillose. What is that? Turns out that lots of mosses have cells that have little bumps. Some lots of bumps and some with only one. Some on one side of the leaf and some on both. You get the picture–another character to learn, observe, and compare to others. This last part is the hard thing to do if you have little or no experience. There are many ways to look at the surface of the leaves but one I’m finding to be pretty reliable is to simply put a small sample of the shoot with leaves whole and observe at various magnifications. However, I didn’t even do this on the first go–having noticed that the leaf surface when dry kind of sparkled I assumed the leaf was papillose. I could always go back later under the scope. See what I mean? Also, note the kind of silver-haired tips to some of the leaves–definitely not Leskea.

Using these shortcuts with Churchill’s key, I ended up with Lindbergia brachyptera which is closely related to Leskea. Having been burned before, I wasn’t ready to commit but I had a place to start. I googled Lindbergia brachyptera and ended up with two sites that I have quite a bit of confidence in and that include images. The Ohio site: https://ohiomosslichen.org/moss-lindbergia-brachyptera/ and Mosses of the Gila site: https://wnmu.edu/…/gilaflora/lindbergia_brachyptera.html Both sites have photos much like I take with my scope so I can do some comparisons. The first thing that hit me on the Ohio site was the silvery grey leaf tips. Ooooo, I think I’m getting closer.

At this point, I decided to see if the plant was part of the Northern Forest Atlas’ Digital Atlas of Mosses. https://northernforestatlas.org/…/15/moss-digital-atlas/ This is an amazing resource. Jerry Jenkins and colleagues have created one of the truly great moss resources. Of course, it is centered on Northern Forests but like I told Jerry last summer at the workshop, I think that over 90% of the moss species in KS are included–at least to genus level and probably over 90% here in eastern KS. Sure enough, Lindbergia is included in the atlas. If you are harboring an interest in mosses you need to download this resource. I’m pretty sure I can get permission to post these photos of Linbergergia but they do ask that we seek that permission to post to a website. So you’ll just need to go download and look. At any rate, these images pretty much created a slam dunk along with the descriptions such as spreading leaves when wet, bristle tips when dry, habitat, and size.

In addition, while reading the text, I found out that Linbergia is not at all common–perhaps even rare back east. No wonder it wasn’t listed in my other resources. I decided to look up some papers on Lindbergia and found this general pattern rare in the eastern U.S. and common in the western part of its range, read KS, MO, and IA. Several papers suggested that the moss was probably a lot more common than thought in other parts of the range but was largely overlooked. Why? Because it tends to grow in clumps of other species. I’m starting to feel really good. BTW, other resources verified that the moss is relatively common in KS–on trees.

BTW, it is the little bumps that make the surface of the dried Lindbergia kind of sparkle which you may be able to see in this image where I placed three mosses found on the piece of bark side by side. Lindbergia is in the middle. Compare that to the Entodon–which doesn’t sparkle because it is smooth.

Finally, one last confirmation. I went to the definitive, technical source the Flora of North America. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1… and looked up more info on Lindbergia, again looking for even more confirmation. I decided I’m pretty confident at this point but should I be? I’ve only found this on this one piece of bark that I found on the bridge.

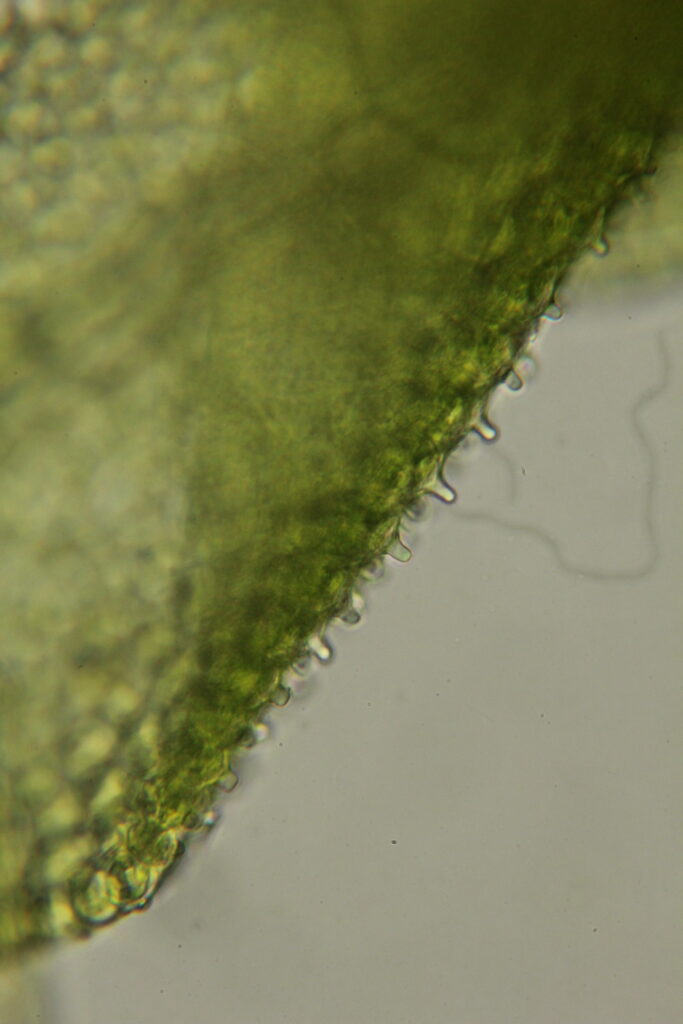

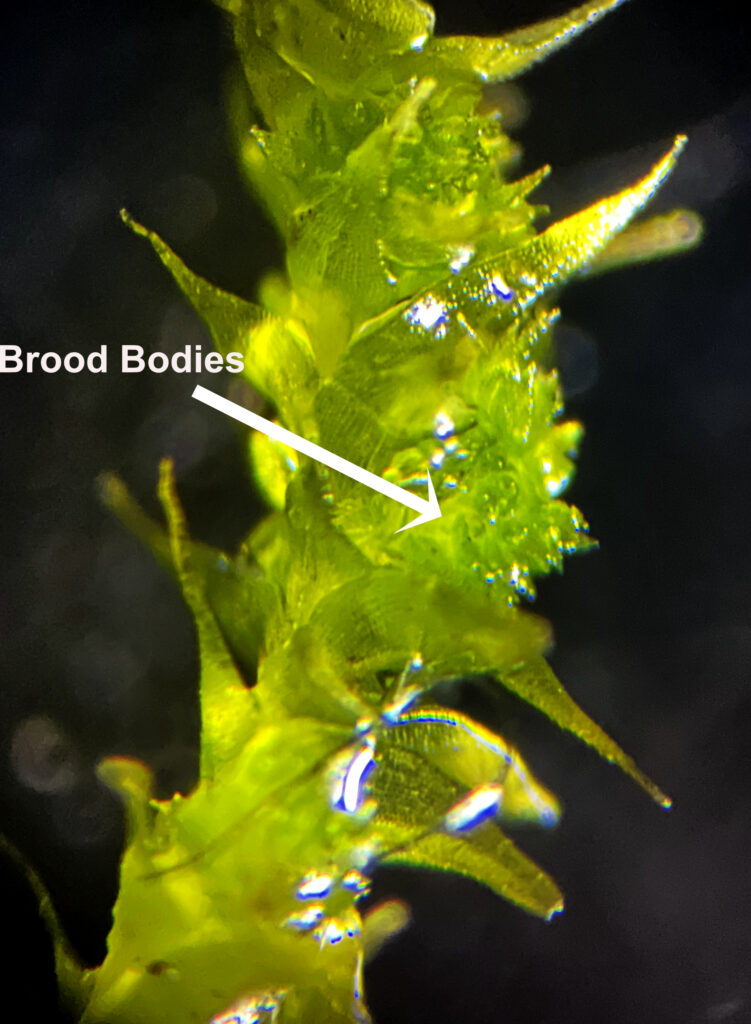

I had read on a couple of sites that there were brood bodies to be found where the leaves attach to the stem on some stems. Brood bodies are miniature moss plants ready to break off and propagate new individual mosses. I had not seen those but I sure thought I should so I went looking. Sure enough, I found brood bodies just as predicted. More confirmation. Getting to identification for a new moss is a heady experience that is enhanced by finding more confirming diagnostic characters. What makes this an almost euphoric experience is the self-checking you do on your knowledge and reflecting on the entire process.